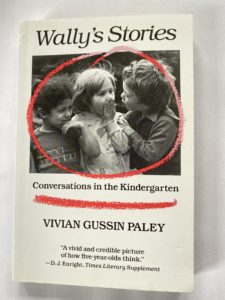

I’ve been thinking about something Vivian Paley once wrote in her book Wally’s Stories Conversations in the Kindergarten. She said,

‘The adult should not underestimate the young child’s tendency to revert to earlier thinking: new concepts have not been ‘learned’ but are only in temporary custody. They have been glimpsed but are not in permanent possession.’

Paley, V.G. (1981), Wally’s Stories Conversations in the Kindergarten, London, Harvard University Press.

It’s a wonderful bit of advice and it applies so well to the concepts we teach in Sounds-Write. When we teach that we can spell a sound with two letters, as is the case with < ff >, < ll >, < ss > and < zz >, we go on to recycle the idea when we teach CCVC words in words such as ‘smell’ and ‘sniff’, before teaching the consonant digraphs < sh >, < ch >, and so on.

Now here’s the rub. Once they have started teaching the Extended Code and because they are teaching that we can spell a sound in more than one way and that many spellings represent one sound, many teachers ‘forget’ to persist in reminding their students that we can spell sounds with one, two, three or four letters. As Paley implies, the idea presented in one particular context has only been ‘glimpsed’ and isn’t yet in permanent enough custody for it to be applied to other contexts. For example, the digraph < oa > bears no resemblance to the consonant digraphs, yet it is still enfolded within the overarching idea ‘two letters, one sound’, an idea that generalises right across the code.

When, later, we are teaching the word ‘psychology’, we ‘make sense of’ the spelling of /s/ by pointing to the spelling < ps > and saying, “This is the way we spell /s/ in ‘psychology’. It’s two letters but it’s just one sound.” Of course, by the time a student is older, you can go into the etymology of the word and examine its morphology, but the simplicity of the idea ‘two letters/one sound’ is a powerful way of thinking about the sound and the spelling. What might previously have been viewed as a string of random letters, now becomes a recognisable singular unit representing an individual sound.

Paley reminds us that even though we may have taught something explicitly and that it appears to have been learned, without numerous reminders of a concept’s relevance and application in other situations, without deepening it in a rich variety of different contexts, it may quickly fade from view.