Phonics offers everyone, from the child beginning to learn to read and write from the moment they enter school to the most experienced reader, a clear and simple strategy for reading and spelling every word in the English language.

Although most people accept that phonics is a very effective way of teaching young children to read, very few of us stop to think about whether it has any application to adult reading and spelling. This is because everyday material contains words which we, certainly if we are skilled readers, have encountered many times before. But what happens when we come across words that don’t normally inhabit the texts we read and, perhaps, need to write about.

Some months ago, I was reading about the Longitude Prize, which aims to tackle the increasing and, some say, potentially life-threatening problem of the growing levels of antimicrobial resistance. The future of our health is going to be compromised if harmful bacteria continue the current trend of developing resistance to antibiotics, and if the development of new antibiotics continues to be slow.

One of the ten most antibiotic-resistant resistant strains of bacteria on the Longitude list is Staphylococcus Aureus*.

Most people, even people who consider themselves to be excellent readers, would probably have had to think fairly carefully about how to arrive at a working pronunciation of the word if they had never seen it before. Spelling it would present even greater problems. Yet, applying exactly the same kinds of techniques we teach children in the early years to tackle ever longer and more complex words is remarkably effective.

Most people, even people who consider themselves to be excellent readers, would probably have had to think fairly carefully about how to arrive at a working pronunciation of the word if they had never seen it before. Spelling it would present even greater problems. Yet, applying exactly the same kinds of techniques we teach children in the early years to tackle ever longer and more complex words is remarkably effective.

My mother, who spent a lifetime as a nurse, used regularly to refer to the bacteria as ‘staff’, though she did have to know how to be able to write it in some of her reports. If one adopts the strategy we use in phonics to break down this word and re-assemble it, we do something like the following:

Sta phy lo co ccus. In the first syllable ‘sta’ is comprised of the sounds /s/ /t/ /a/. The second syllable ‘phy’ is comprised of two sounds /f/ and /i/. The < ph > is a two-letter spelling. The third syllable ‘lo’, when spoken normally, or as normally as a nurse or doctor might say it in everyday conversation, is comprised of the two sounds /l/ and /schwa/, the spelling < o > representing the schwa or weak vowel sound. The fourth syllable ‘co’ is comprised of the sounds /k/ and /o/. The fifth and final syllable ‘ccus’ is comprised of three sounds : /k/ /u/ /s/.

As you can see, I’ve highlighted the two spellings in the word which are comprised of two letters but which represent a single sound. As the word is derived from Ancient Greek, we have the spelling < ph > for the sound /f/, and we have the spelling < cc > for the sound /k/.

If the word were to crop up in a text a class were reading and which the children might be expected to write about and also see co-occur is similar texts in the future, it would be important to teach it. And, even though the word is domain-specific, enabling a class to be able to read as well as to spell complex words such as this one is essential.

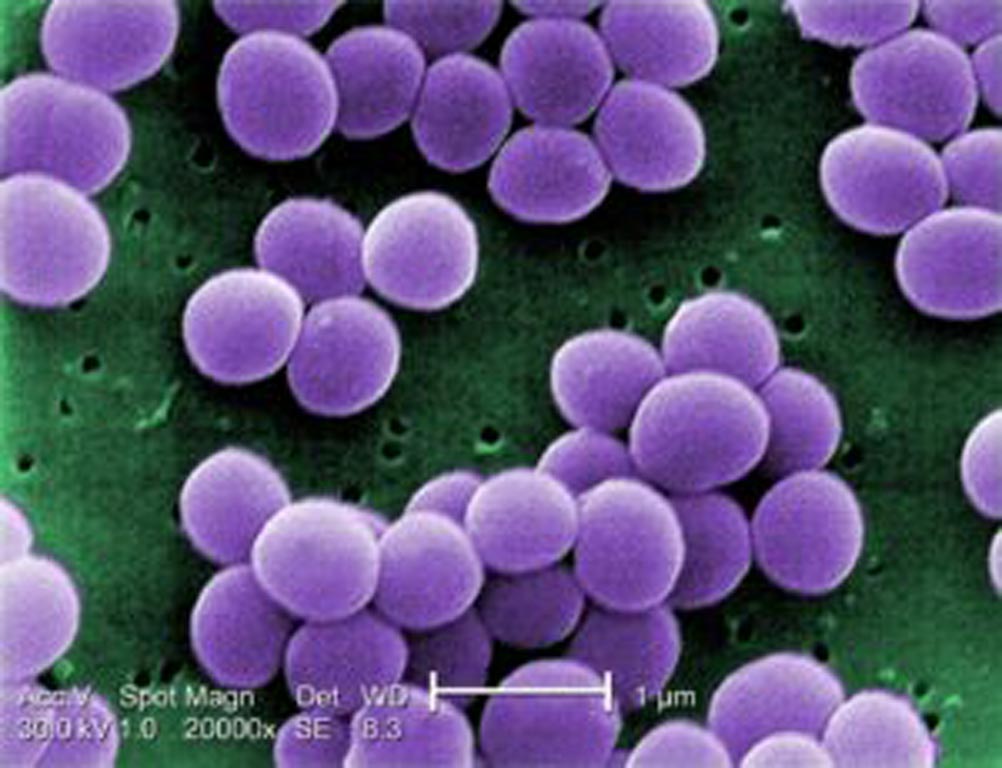

As teachers, we are always looking for opportunities to enhance and extend learning beyond the boundaries of single items and we would almost certainly want to look at the etymology of such words. Tracing the roots of words certainly makes remembering them and remembering how they are constructed easier. In the case of ‘Staphylococcus’, ‘Staphylo-‘ is derived from Ancient Greek and means ‘bunch of grapes’. ‘-coccus’ comes to us through Latin from the Greek kokkus, meaning ‘grain, berry’. Put the two together and we have a bunch of what look like grapes or berries comprising what are the Staphylococcus Aureus bacteria.

You may think that one couldn’t possibly spend time dealing with all the elements in the analysis of this one particular term. The truth is that even children in Key Stage 1 and who have been taught a high-quality phonics programme would have no difficulty in performing the same operation with this word. In addition, almost invariably, this kind of solid knowledge is cumulative and applies across a range of different domains.

The problem lies not in teaching children (at whatever level) how to read and write long, complex words; the problem lies in making sure teacher subject knowledge is up to the task.

*Please note that we often break words into syllables in slightly different ways. Nevertheless, however wesyllabify a word, we should all arrive at the same number of syllables.

Thanks for use of the image to: Content Providers(s): CDC/ Matthew J. Arduino, DRPHPhoto Credit: Janice Haney Carr – This media comes from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Public Health Image Library (PHIL), with identification number #11157. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7469288