So, after much kerfuffle and a huge amount of opposition from a wide range of (mainly) university academics, the teaching unions, and assorted self-proclaimed pundits, South Australia has just reported the results of an opt-in version of the Phonics Screening Check. It was taken between 7th and 18th August 2017 and it was exactly the same Check as was used in England in 2016.

So, after much kerfuffle and a huge amount of opposition from a wide range of (mainly) university academics, the teaching unions, and assorted self-proclaimed pundits, South Australia has just reported the results of an opt-in version of the Phonics Screening Check. It was taken between 7th and 18th August 2017 and it was exactly the same Check as was used in England in 2016.

According to The Conversation (Australia), it has been an eye-opener. Fifty-six schools volunteered to take part in the trial. Included were 4,406 pupils and, of these, only 15% managed to score over the threshold mark of 32 out of a possible 40. By contrast, the figure is now 81% in England. So, quite a discrepancy! However, it needs to be said that 52% of the children taking part were in Reception; the other 48% were in Y1 and took the test about three-quarters of the way through their second year of schooling. [In England, the Check is taken in the first week or so of June, or about a month and a half before the end of the school year.]

Digging down into the figures a bit, Reception children were, on average, able only to read 11 words correctly. One fifth – is this the 20% figure we see so commonly recurring? – of the cohort were unable to read any words correctly; whereas around 4% of the Y1 children were unable to read a single word correctly. At the other end of the scale, one in six or almost 17% of Year 1 pupils read between 36 and 40 words correctly.

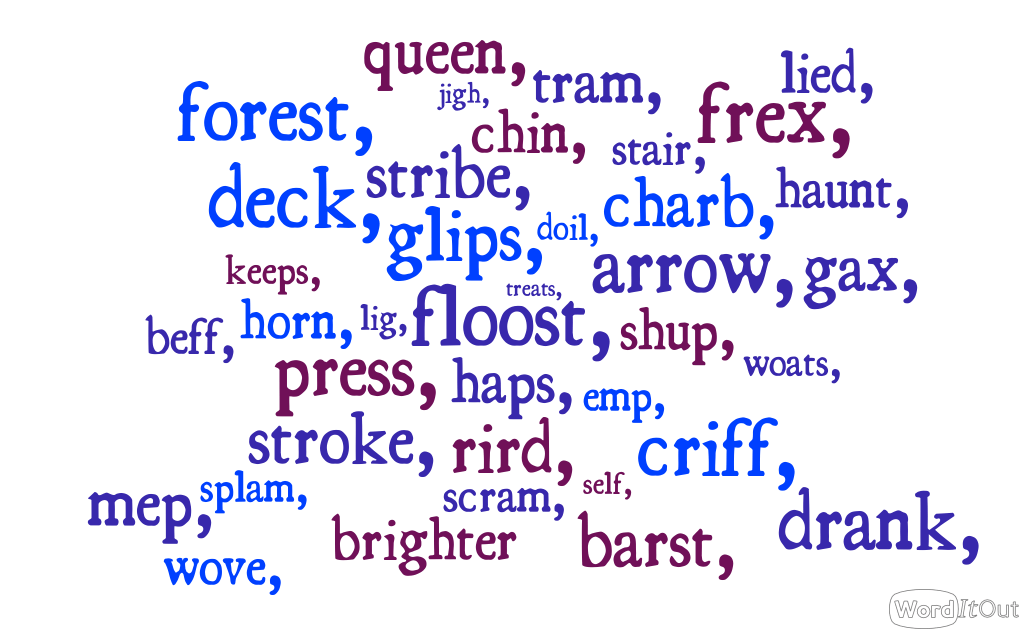

Quite why the South Australia Department of Education and Child Development decided to give the check to children in Reception is really a mystery to me. All that you learn from giving children in Reception, who are still not more than three quarters the way through the year, a screening check that was designed for use in England at the end of Year 1 is that they can’t do most of it because there hasn’t been time to teach them the required code knowledge, skills and conceptual understanding of how the code works. As the report states, a full 25% of children in Reception had dropped out by the sixth word in the Check and only a fifth of the cohort was able to read the seventh word ‘doil’.

The data seems to directly contradict the claim made by many academics that things are fine, that teachers are already teaching phonics, and that there was never any need for the check. As one of the sub-headings makes clear: many students have very low decoding ability after eighteen months at school. What this means is that there’s a much greater chance for many children learn maladaptive practices, such as guessing, and to grow up totally confused about the nature of reading.

Although there were a number of methodological changes to the PSC in England, the South Australia Department of Education and Child Development seems satisfied that the checks are broadly comparable. I’m not at all convinced by this. For example, one of the changes to the rubric of the Check was the so-called ‘stop’ instructions, about which, according to the report ‘there was confusion’. The ‘stop’ instruction advised teachers that the Check should stop after three errors. This was variously interpreted, which clearly meant that the teachers were not administering the same Check.

However, my objection would be that what might by some teachers have been deemed ‘simple’ might actually be ‘complex’ and what was regarded as ‘complex’ might be ‘simple’. For example, I would regard the introduction within the Check of alternative spellings of the vowel sound /oe/ (‘woats’, ‘stroke’, ‘wove’, and ‘arrow’) as more complex than a word containing three adjacent consonants, such as ‘scram’. ‘Scram’ is comprised of five sound-spelling correspondences (SSCs) all of which are Basic/Initial Code SSCs, comprised of single letter spellings of sounds. Children ought to be taught to read and spell such words to mastery level before going on to learn different ways of spelling the vowel sounds. In fact, many children taught using a very high-quality phonics program would be able to manage CCCVC words with relative ease after two terms in an English school.

I don’t propose to rake over the coals on this. Suffice it to say that if South Australia is representative of the rest of Australia – and there’s no reason to suppose this shouldn’t be the case – then there’s one hell of a lot of work that needs to be done and done quickly.

Instead, I want to give both teachers and parents an idea of what needs to be taught if a child is going to cope with the test. I’d also add the rider that I think the Check is a very good thing in that it lets principals, teachers, and parents know exactly what a child is able to do in terms of being able to link spellings to sounds (reading) and being able to perform the fundamental skills of segmenting and blending required to read the words in the check.

The check consists of 20 pseudo words and 20 real words, although half of the real words are intended to be less frequently encountered in text.

One problem I need to highlight with this and every Phonics Screening Check devised in England is that the Check follows the order of sound-spelling correspondences taught in Letters and Sounds. This can be a problem for a number of reasons:

- In L&S, the skills of segmenting, blending and phoneme manipulation are not taught robustly enough, as I’ve hinted above. Amazingly, L&S makes teaching single-syllable words containing adjacent consonants optional. This is folly, especially as we know that there is always a significant number of children who struggle with them.

- The authors of L&S seem oblivious to the fact that children find it easier to segment and blend CVCC words before they are able to handle CCVC words. Thus, you will see in the Phonics Screening Check that CCVC words come before CVCC words. In a check in which the teacher stops a child after three errors, as they are allowed to do in the SA check, this can make a difference.

- After teaching a Basic/Initial Code, the L&S program goes on to expect teachers to teach one spelling of a sound at a time, hence the inclusion of the sound-spelling correspondences < ar > for /ar/ and < or > for /or/ early on in the check. Everything I’ve seen in schools convinces me that the encouragement to teach only one spelling of a sound pushes children on too fast before they have mastered the necessary skills and elements of conceptual understanding they need to learn in the Basic/Initial Code. It can also encourage children to spell vowel sounds for which they have been taught only one spelling to spell every word containing that sound using the single spelling they’ve been taught regardless of whether it is the correct one or not. And spelling words incorrectly over and over again is definitely not a habit to be promoted.

Unfortunately, most of the people commenting on the South Australia Check will be people who are completely naïve about instruction. They don’t understand the fine-grained detail of phonics teaching when, in fact, successful phonics teaching is all about the details: what is introduced, how much is introduced at any one time, how much practice is required, how much spaced-practice should be used, how common errors can be corrected to the benefit of the child, and so on.

Tomorrow, I shall be looking at the detail of the Check, the assumptions behind its construction, and what it tells us about how effectively teachers are teaching phonics in South Australia.