While there has been much interest in cognitive load theory (CLT) – Dylan Wiliam, quoted in Greg Ashman’s blog Filling the pail, says he thinks it is ‘the single most important thing for a teacher to know’ – very little has been written that specifically address early years teaching.

One aspect of CLT discussed by Greg Ashman this morning in his post ‘(Un)Desirable Difficulties’ is that of ‘element interactivity’. What the idea behind element interactivity proposes is that we need to account for all the elements needed to be processed in parallel in working memory during a task. Accepting that the theory is somewhat controversial, what might be the implications of teaching a phonics lesson to a class of children for the very first time?

Here’s the scenario we encourage teachers to use in Sounds-Write:

There are thirty children sitting on a mat looking at a teacher who is standing at the side of a whiteboard. On the whiteboard, she places three sound-spelling correspondences (SSCs) – all the sounds-spellings needed to build the word ‘sat’.

Of course, some children will arrive in front of that whiteboard with prior knowledge of the sound-spelling associations. What they will almost certainly not have seen is the way in which the lesson is set up. They will also probably not be familiar with the processes which are designed to teach the skills of segmenting and blending. Other children in the class may only recognise a single sound-spelling correspondence because it’s in their name and this has been shown to them before. Still other children will be confronted with this ‘game’ for the first time and will, therefore have no prior knowledge.

Assuming that the word ‘sat’ is already within the children’s spoken vocabularies – the teacher would need to determine this before the lesson and pre-teach it if necessary – the lesson begins with the teacher placing the SSCs on the board, jumbled up and out of order. Underneath these, she draws three lines, long enough to accommodate the Post-Its/laminated squares on which are written the SSCs.

Now, drawing her finger slowly over the lines, she asks the children to listen carefully for the sound they hear when her finger is over the first line as she stretches out the word ‘ssssssssat’, placing emphasis on the /s/. If done a number of times – to give the children plenty of time to listen and to process what is being asked of them – there will be children who can tell the teacher that the sound they can hear when the teacher’s finger is under that line is /s/. And the teacher will agree and ask everyone to say /s/.

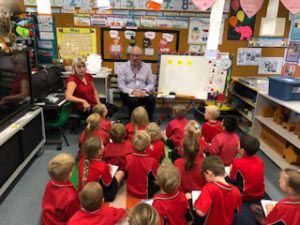

In this short video sequence, you can see Hannah teaching the word ‘sat’ to a class of children who are about to enter Reception in the new academic year at St George’s CEPS.

Bearing in mind that there will always be at least one child sitting in the class who can link the sound to the spelling, the teacher can now ask a child to come forward and to choose which of the SSCs represents the sound /s/. The child is asked to say the sound as they pull it down onto the line and everyone in the class is asked to join in. This is exactly what teachers talk about in maths as the ‘worked example’.

Using exactly the same process for the remaining SSCs, once the word has been built, the teacher, using her finger to gesture, points separately to each SSC and asks the class to say the sounds and read the word. She will then ask one of the children to say the sounds and read the word: /s/ /a/ /t/, ‘sat’. Now, the teacher asks four or five other children to do the same.

This is only half of the lesson and you can see how the rest unfolds by looking at this post.

So, what is it that the children have had to process? First, they’ve been presented with a game they’ve never played before. They’ve had to connect sounds to spellings and they’ve said the sounds and read the word. For children who have prior learning, connecting sound to spelling is easy, though they will probably have had to think about the segmenting and even possibly the blending activity.

For children with no prior learning, there’s a lot going on in this simple lesson. However, they will have been introduced to three SSCs in the context of a real word, and this gives the activity a real purpose.

Literate adults would have problems learning more than three SSCs in learning, say Greek, where the Roman alphabet isn’t used. On top of that, they have to learn the way in which the ‘game’ is played and process the way in which all of the separate elements interact.

If the lesson is introduced first thing in the morning, the word ‘sat’ can be re-introduced, briefly, in the afternoon as a reading activity: “Who thinks they can read this word?” A child with prior learning or an excellent memory can step forward to read it, after which the teacher will once more go round the class calling judiciously on children to say the sounds and read the word.

So, the idea of ‘element interactivity’ makes perfect sense to me and should forewarn us not to introduce too many different elements into an activity at the same time. However, once the format of the game has been established, only the content needs to change and that content can be delimited and controlled.

On the next day, everyone is ready to take on ‘mat’.