The strange case of the word ‘yacht’. This old chestnut comes up on a fairly regular basis and is cited as an example of how not all English words are decodable.

In truth, the word presents us with more of a challenge than many others. However, holding to the notion that every word incorporated into the English language is comprised of sounds and that all sounds have been assigned spellings, ‘yacht’ contains three sounds /y/ /o/ and /t/. How then can sounds be linked to spellings in a way that would enable young learners to remember how to spell it?

Well, the word came up in the round in a school I was working with a few years ago. We ’embarked’ on an exercise in seeing how best to link the sounds of the word to the way it is spelt. I asked the class, a Year 4 who had been doing Sounds-Write since they had begun school, to work in small groups and to see what they could come up with. They proposed two choices: first, y ach t; and, y a cht. They then voted on which of the two they preferred. The answer was the second choice. [My vote went to the first!] This was, they argued (logically) because the sound /o/ can be represented by the spelling < a > in lots and lots of words when it follows the sound /w/. Having completed this short exercise, to implant it into their memories, they all wrote it and said all the sounds, before reading it back again. [This activity should be repeated a week or so later.]

Of course, I wouldn’t expect a young child to be able to read or spell the word without some support. And, if it came across the bows during a lesson, I’d deal with it there and then, or, if it proved to be too intrusive, save it to discuss later. This is how best to extend code knowledge in KS2/3/and 4.

Talking of it coming across the bows, where does the word come from? In actual fact, it is derived from Dutch. In early modern Dutch, a ‘jachtschip’ was a pirate ship. Readers of German might also recognise the word from ‘jӓger’ or ‘hunter’. In Dutch, the word sounds remarkably like the English word, except that the < ch > represents a separate sound, which sounds a bit to my ear like some Liverpudlians would say /k/ in the middle or at the ends of words: thus, /y/ /a/ /k+/ /t/.

Talking of it coming across the bows, where does the word come from? In actual fact, it is derived from Dutch. In early modern Dutch, a ‘jachtschip’ was a pirate ship. Readers of German might also recognise the word from ‘jӓger’ or ‘hunter’. In Dutch, the word sounds remarkably like the English word, except that the < ch > represents a separate sound, which sounds a bit to my ear like some Liverpudlians would say /k/ in the middle or at the ends of words: thus, /y/ /a/ /k+/ /t/.So, what’s my point? Well, I have two actually. The first is that not only is the word decodable and encodable, it is also an example of how, even at a bit of a stretch, English is comprehensive. That is to say that it can easily incorporate pretty much any loan word from any language even when the loan word is a challenge for us to pronounce and, as a result, forces us to anglicise it. My second point is that, having analysed the word in the way suggested above, children are far more likely to remember how to spell it in the future. And, if as a teacher you find that you’re stumped as to the derivation of a word, ask the children to look it up online.

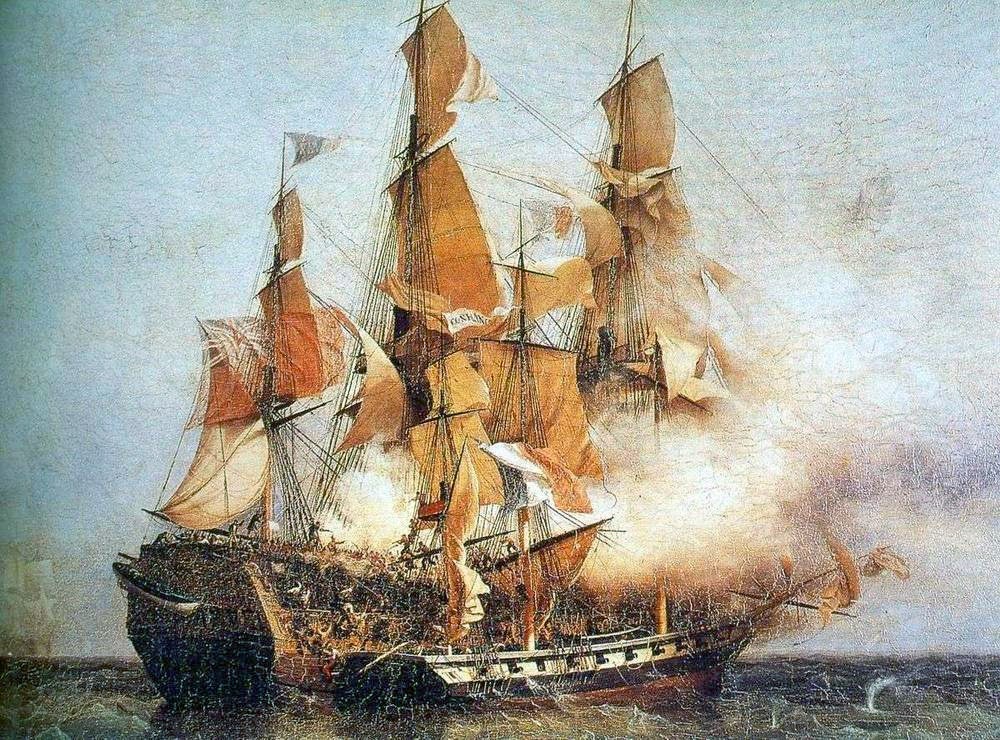

Thanks for featured image to: Jacob van Strij – Het Jacht van de kamer Rotterdam.jpg

What serendipity!

Tonight I was reading to LittlePaperMover and the word yacht came up. I thought the word was fascinating from a SP point of view, and tried to work out the sound representations. (I am with your pupil's as i thought it was Y-a-cht, for the same reason they did. )!LittlePaperMover was incredibly unimpressed with the phonics lesson and put her head under the duvet and la-la-lahd until I shut up and got on with the story.

Tomorrow I shall tell her that not only is she an ungrateful small person but that yacht is a pirate word. She does love a pirate. She might learn how to spell yacht.

Papermover

Hi Papermover,

Serendipidous indeed! 'Yacht' is pretty low frequency I would have thought but it does have a habit of popping up in children's stories.

If it appears in the middle of a bedtime story, I would definitely leave it until the following day to talk about. As a way of doing it, you might word build it, which would leave the spelling cht for /t/ until last – setting LittlePaperMover up for success. Then, when you've built the word, point to the a and say that it is /o/ as in words like 'was', 'swan', 'swallow', etc. When you point to the cht, you tell her that it's a one-off spelling of the sound /t/. And, then you can talk about derivation or pirates, a technique which is often a useful mnemonic.

Similarly if it comes up in the middle of a lesson at school, where at KS2, for example, the focus would probably be on comprehension. The teacher should supply the word and return to it later or on the following day in a phonics session.

Anyway, thanks for telling us about your experience. I look forward to some follow-ups.

Dear John,

You and I mean different things by “decodable”.

For me, a decodable word is one which can be read aloud (“decoded”) even if it has never been seen before. On this definition, yacht is not decodable.

Since you think yacht is decodable, you must have a different definition of “decodable”. What is it?

A second example: take the word fleury. A real word, but I expect you haven’t come across it before. The correct way of breaking it up is f l eu r y. But even though I have told you that, I don’t think you will be able to read it aloud correctly. That shows that it is not decodable (in my sense).

Best wishes,

Max

Hi Max,

We certainly do have different understandings of the word decodable.

For you, 'a word is decodable if it can be read aloud even if it has never been seen before'.

For a child in reception, the word 'vet' may not be decodable if, for example, the child has not yet been taught that v represents the sound /v/.

So, the ability to decode partly depends on the level of code knowledge a child has. I say 'partly' because decoding ability also depends on the skills a person brings to their reading. Can they segment and blend proficiently enough to be able to use their code knowledge efficently?

And then there's the question of a person's understanding of how the code works. So, do they understand that sounds can be spelled with more than one letter, that sounds can be spelled in (often) multiple ways, and do they also know that many spellings can represent different sounds?

Given that all of these aspects of decoding have been well taught, I would fully expect some Y2 children and very many Y3 and above pupils to be able to decode 'yacht' successfully, although they may well baulk a little when it came to thinking about remembering how to spell it. That's where the teaching come in!

I am also a little surprised you patronise me by assuming I wouldn't be familiar with the word 'fleury' or be able to read it. But, you know what, even if I hadn't been reading words like this since I was in primary school, I would almost certainly be able to decode the word because of the similarity with other spellings of /er/. Of course, it goes without saying that any pupil learning French would be able to handle it after learning 'travailleur', 'meilleur', or, perhaps, the more obvious 'fleur'.

I agree with you John … I like the first Y-ach-t and thought that straight away … probably because I am of the right age to be a big U2 fan. I'll tell my children about "Achtung Baby" to help them remember :).

Thanks again John for making English decodable …

Hmm. Actually, yacht isn't a "pirate ship" word, it's a "hunter of pirate ships" word. (Today's mega-yachts might be considered private pirate ships, but that too iw a whole nother story.)

The only stange thing about the word "yacht" is that it is considered a "strange case." Your first point is well-taken: The English language can easily incorporate pretty much any loan word from any language. This is a strength/asset of the language, not a weakness. It's what makes English the most widely used language in the world. However, there are a number of words, mostly personal and place names, whose Alphabetic Code correspondences follow the loan word history. So if the name of a city or person is written as Jaeger, it could be spoken as yayger, yogger, jayger, or jogger. And the pronunciation of the "er" would vary depending upon whether it was BritSpeak, YankSpeak, or some other Speak. The "assignment" of the correspondences is by convention, but the word is decodable whatever the convention, and once you know the convention, it's "no problem."

Had history gone differently, we could be writing "yacht" as "jacht," and if we are txtg, keying the word as "yot" is OK. The Correspondences are the link between the written and spoken language, but the action is in the Correspondences, not in the sounds or the symbols per se.

Your second point: having analysed the word in the way suggested above, children are far more likely to remember how to spell it in the future is arguable.

1. Some kids will have encountered the word in spoken or written communication and will be able to read it without any additional instruction. For those who can't, saying, "The pronunciation here is 'yot.'" is the the only "reading instruction" needed.

2. Kids are rarely going to have occasion to spell the word, and when they do, there are many alternative words they can use. "Ship" would work for them in most situations.

The nautical Technical Lexicon is large, and there is much more ambiguity in the definition of the word "yacht" than there is in its Alphabetic Code correspondences. Is a dinghy a yacht? How about a cruiser? Is a yacht a boat or a ship? These distinctions are relevant to composition instruction and to Thesaurus use, but they are unproductively redundant in reading instruction.

The broader point is that all English words are decodable. If a word isn't decodable, it's unintelligible. Fxjk is not decodable. F**k, though is decodable, given that you know some specific conventions beyond the Alphabetic Code. Those conventions are no more complicated than those entailed in punctuation marks, or in contractions, abbreviations, and wingdings. But if you haven't been taught the conventions, you will encounter difficulty in reading the text.

The standard definition of "decodable" can easily be checked by googling the term. (The definitions matches your definition.) However, there are "non-standard" definitions of "decodable, such as Max's. When the referents for the term are clear, as in this thread, there is "no problem." But there are big communication problems with non-standard terms in general and with the term "decodable" in particular. Few texts that are proffered as "decodable" actually conform to the standard definition.