Talk to anyone today who was taught to read through i.t.a. (Initial Teaching Alphabet) and they will almost invariably tell you how they’ve never been able to spell correctly since.

As i.t.a. was more or less abandoned in the sixties/early seventies (though it did cling on for much longer in some places), many of today’s generation of teachers will never even have heard of it except from their parents or grandparents! So why write a blog posting about it?

I’m writing about it because it did, at first sight, appear to be a great idea. At the same time, as the title of the post suggests, it was a disaster – because so many children were left floundering it its wake.

Starting with the ‘great idea’ bit, it was conceived by James Pitman, grandson of Isaac Pitman, developer of the famous shorthand system of note-taking still in use today. What James Pitman thought was not dissimilar from the ideas of Stephen Linstead, Chair of the English Spelling Society Spelling reform. Pitman thought that if he could produce a single symbol for every one of the forty-four sounds in English, children would have a simplified and very easy system to learn. Doing so would give us a writing code not unlike Italian or Spanish.

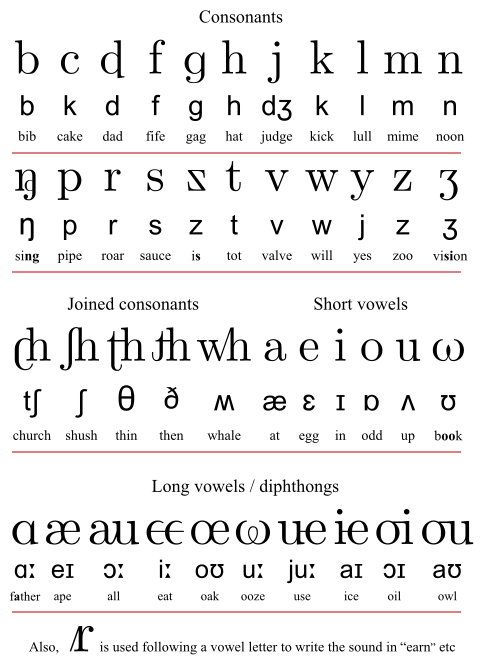

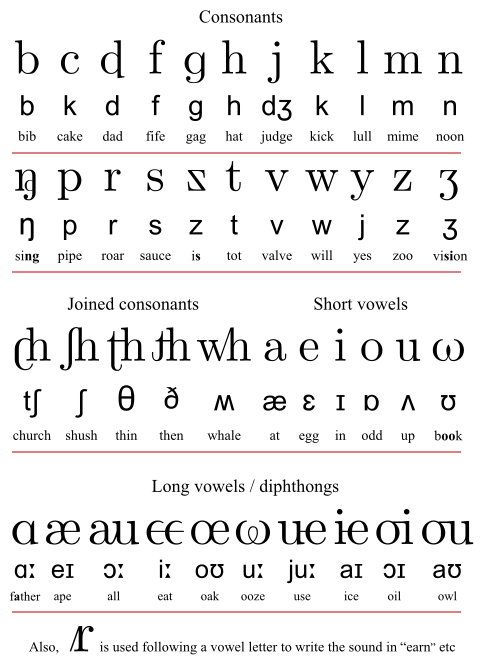

Most of the single letter spellings, the one-to-ones remained the same. So, the spelling in ‘bat’ remained the same as in our accepted orthography. Where the system differed was in many of the two-letter consonant and vowel spellings. Thus, Here’s an example: /th/ (unvoiced) in the word ‘thin’ was spelt q; /th/ (voiced) in the word ‘this’ was spelt d; the sound /ae/ as in ‘gate’ was spelt æ; and, the sound /oe/ in ‘goat’ was spelt œ.

The most obvious problem with such a system is that, at some point, the transition to our accepted orthography must be made . In the sentence ‘I hav a goet.’ above, the spelling of /v/ in ‘have’ is commonly spelt ve at the ends of words and the spelling of the sound /oe/ in ‘goat’ is oa. For children to make the transition, the teacher has to make explicit to children that, in English:

· we spell sounds with one, two three or four letters

· sounds can be spelt in multiple ways

· many spellings represent more than one sound

The teacher also has to teach all the various common ways of spelling sounds for reading and spelling, and they need to know how to teach that many spellings represent different sounds and the skills to enable them to use this knowledge when reading and writing.

Because hardly any teachers knew how the transition to accepted orthography should be taught, many children were left struggling to work out the logic of the alphabet code. Teachers in (the then) junior schools (KS2) found themselves confronted with children writing what seemed to them like gobbledegook.

The next problem with i.t.a. was that it presented the spellings for the sounds of someone with a Received Pronunciation (RP) accent, which is not the accent of many speakers of English. So, it didn’t make sense to speakers of other varieties of English. In addition, aside from also violating the principle that it is never a good idea to teach what later needs to ‘un-taught’, no-one for a moment believed that all existing written materials should be re-written in i.t.a. This meant that after learning to read and write i.t.a., children had to be taught how the code works.

Today’s would-be spelling reformers peddle what is essentially the same line: simplify spelling and learning to read and write English will be much easier. As I’ve pointed out here, the idea is a pipe dream. Many previous attempts have been made and they all founder on the rocks of different accents of English and on establishing an agreed system of spelling the forty-four sounds in the language, including the most common vowel sound, the schwa.

There is one reason and only one reason for the spelling reformers’ confusion – instead of starting with the sounds of the language and teaching children the different ways of spelling those sounds, they start from spellings. Spellings, they seem to think, ‘make’ or ‘say’ sounds. They don’t. We are dealing with a symbolic system: spellings are symbols for sounds. Once this becomes your starting point, you have an anchor for all your subsequent teaching.

Below is the i.t.a. chart, which you’ll also find on Wikipedia here.

Below is the i.t.a. chart, which you’ll also find on Wikipedia here.

Rite 2 th last par, I'd say. The ankor is th Alpha Code, & th akshon is in th CORRES btw the ltrs & th snds tht comprise th wds, not in the ltrs or snds per se.

The thing is, English "spellings" are symbols for "readings" not symbols for "sounds." Children enter school speaking prose, but but few know how to read speech, and that communication is what reading instruction is all about. The English-speaking world has yet to devise instruction to reliably teach all kids how to do this. The UK is on the forefront of accomplishing this task, and more than 600 schools in England are doing it. Curiously, we don't know what distinguishes the instruction in these schools from that of schools that aren't, but "some day" that information will come to light.

I was taught by ita and got on really well with it. I'm amazed how people find it so hard to read. I'm now a teaching assistant and find the way phonics is taught now much harder. I don't really remember a transition between alphabets. I still recall the reading books we had including Janet and John books. I still have some of them.

I was taught ITA and got on well with it. The problem came when I later came to read normal English I really lost my confidence. Sounding out words like stomach and hearing the whole class laugh at my ignorance

To this day I struggle with spelling even quite simple words. I wonder how I might have done if I had not gone through this ridiculous system.

I still feel self-conscious about my inability to spell.

I wonder if anyone ever sued the educational services for this?

I was irritated that, even though I could read fluently at age 5, and I was allowed to use the adult library at age 6, I still had to go through ITA.

Just fancy, Archibald, you learned to read and write your name – no doubt with expert help from your mother/father/aunt/etc. and then you have to learn to spell it in some mysterious code, half of which makes sense and half of which is simply incomprehensible. And what a name! It sounds as though you came through despite the odds 🙂

I also was taught to read using i.t.a. and I also question my spelling of any word over 4 letters. I have to say that teaching a child to read with an alphabet of 45 letters and 2yrs later tell them that way is wrong we have to do it this way now so unlearn what we just taught you. Silly way of teaching if you ask me. I just figure we were all part of a bad experament and thenk god they aren’t using it anymore. I HOPE.

Well, Jeff, if only the creator of this programme had learned the one thing I never forgot in my training: never teach something you’ll have to unteach later! It was a very bad experiment and you are one of the many casualties.

I’ve struggled my entire working life with spelling, as previously mentioned small words remain difficult to spell. verbal communication, grammar, and punctuation, not a problem, but spelling has always been my Achilles heel.

I’ve been fortunate to reach senior management positions and if provided with an administrator or the aid of spell check have managed well, take them away or need to produce information on a whiteboard !!

Like wise hate having to spell these days

ITA was a complete joke

Know feeling

I started school in 1972 and yes, learned to read with ita. I can remember my parents being appalled by it. However, I didn’t have a problem with it and soon took to reading conventional Ladybird and other story books at home. I do still have some of my schoolbooks from back then and wheel them out every so often to show to people who can’t believe we were taught that way. A change of headmistress in our third year ended ita and brought in Racing to Read and Wide Range readers. To be fair, when it came to moving to junior school, half the class were considered so advanced that we all went straight into the second year, so it couldn’t have been all that bad. I agree it seems a ridiculous system but it worked for us and today I work as a writer and editor.

I also was a victim of ITA. I learned to read at home with engaged parents, unlearned it in K & 1 grade, never was taught the “actual rules” to transition, and now I stand in front of college classes with my Ph.D. and spell like a 2nd grader when writing on the board! I recall building a wooden craft in first grade, painting it up all neatly, and spelling “garage” across the front. I got scolded for not using the ITA spelling. Can you imagine? I remember an even from 45 years ago like is was yesterday. I knew then that the spelling I was learning was crap and got reprimanded because I actually knew how to spell. That teacher and every administrator in that school should have had their licenses revoked (<– those words only got spelled right because of my spell checker!)