Word building is the perfect place to start teaching young children to read and write from the moment they enter school because by so doing we can mitigate the problem of teaching an alphabetic code that is highly opaque. Here’s how:

- word building ensures children understand the direction of the code – from each sound in speech to its spelling;

- it anchors the code in the finite number of sounds of the language (around 44) and not in letters;

- as long as it is grounded in teaching single-letter spellings in simple, CVC words, it sets up an artificially transparent alphabet which makes the orientation of the code obvious and accessible;

- it integrates the teaching of the skills of segmenting and blending as part of the process;

- and, it provides a platform or foundation from which the complexities of the code can be added.

All five bullet points should be seen as the basis for a perfect schema on which to develop reading and writing.

Rather than introduce young children to random spellings (letters), telling them that such and such is this sound or that sound (paired-associate learning – which is very difficult for young children) and then expecting them to retain the knowledge, it’s far better to give the learning a practical context. Word building provides all the elements young children need to learn successfully. It offers the opportunity to learn a limited number of sound-spelling correspondences in the context of a real and recognisable word and in so doing gives phonics teaching both a purpose and a psychological reality: for the child, who already knows what a ‘mat’ is and what ‘sit’ means, word building pulls back the curtain on the mystery of the connection between spoken language and writing.

To start with, anyone wanting to teach word building would do well to introduce children to small whiteboards, pens and wipe-off cloths. Teaching children to become familiar with these items and to get used to drawing lines on their boards, like the one below, is a very useful first step because teaching a child to link sounds to spellings and to manipulate them at the same time as thinking about drawing lines on a whiteboard without prior learning will overburden some children.

For a word building lesson, here’s what the teacher’s whiteboard looks like:

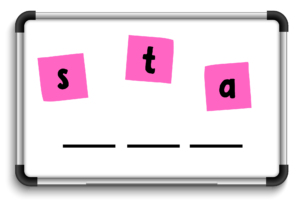

Let’s begin by building the word ‘sat’. We need three Post-Its, laminated squares with magnetic tape on the back, or even squares of paper on a whiteboard if we are teaching the lesson to a small group on a table-top. On these, the teacher writes the spellings, though not necessarily in the correct order because some children are adept at spotting the order in which the sound-spelling correspondences are placed on the board and then they don’t have any cognitive work to do.

The teacher places the three squares, jumbled up and out of order and slightly out of line, like this:

Normally, in a Kindy/Prep/Reception phonics lesson, the children will be sitting on the carpet or at desks with the classroom whiteboard in front of them looking at it as it is above. To some children, it’s likely that, without prior learning, the spellings on the board representing the sounds in ‘sat’ will be new to them. To others, whose carers/family members read to them and even teach them, the spellings will not come as anything new and this will give them a huge learning advantage (prior knowledge).

In the lesson, we are going to be building a simple, CVC word and simultaneously creating a schema for sounds and spellings and hereafter we’ll be building on the schema as we add, cumulatively, more sound-spelling correspondences. In addition to teaching the connection between the sounds in words such as ‘sat’ or ‘mat’, we are also going to be teaching the children the procedural skills of segmenting sounds in words and of blending.

The teacher stands by the board and says to the children, “I’m going to say the word ‘sat’ very slowly. Listen carefully to hear the sounds that make up the word ‘sat‘.” This is scaffolded by the teacher drawing her finger in one sweeping movement under each sound as they stretch out the word, taking care not to pause even ever so slightly between the sounds and thus do the segmenting for the children: ‘sssaaaat’. This should be done so that the teacher’s finger corresponds to each sound as it sweeps under the lines on which we are going to build the word.

The lines are a form of scaffolding which provide a place for children to listen: they give children a simple, physical, locational cue. They also focus the task on exactly what we want the children to be doing. Another element of the scaffolding is the fact that we start with a word beginning with a continuant: both /s/ and /m/ are sounds we can stretch out and hang on to, enabling all children to have the opportunity to hear them. By using gestures – the movement of the teacher’s finger under the lines as she stretches out the word – the teacher is also mobilising what cognitive scientists are increasingly recognise as a form of dual coding which greatly facilitates learning and doesn’t increase cognitive load.

Now the teacher says, “What’s the first sound (gesturing to the first line) you hear in ‘sat‘? Listen to what you hear when my finger is under this line.” And this is repeated several times to afford all children the chance to hear what the teacher is asking them to do.

As already indicated above, the teacher should say the word slowly, but without segmenting it for the children – that’s their job!. (Example: ‘sssssaaat‘) As you the word is stretched out, the teacher slowly slides her finger under the lines corresponding to each sound.

Now she chooses a child to answer. I personally have never seen a Reception/Pre-prep/Kindy class in which there isn’t at least one child who is able to do this. In fact, usually, there are lots of children who are bursting to give an answer. The teacher should choose a child whom she knows is likely to have success and is likely to respond with /s/ and the teacher should say, “Yes, you can hear /s/. Everyone, say that sound, “/s/.” And, all the children say /s/. The teacher is listening carefully to what children are saying and correcting any children who say ‘suh’ or ‘ess’ by pointing to her mouth and modelling the sound /s/.

Pointing to the spellings on the board, the teacher now asks the class: “Which of these is the way we write/spell /s/?” [Notice the accurate, brief and explicit language.] And, she chooses someone to come out to the board and show which one spells ‘/s/’. Having done that, the child pulls the spelling on to the first line and says ‘/s/’ and all the children are encouraged to say the sound as it is pulled into place ‘/s/’. If a child didn’t know, the teacher would simply tell them by pointing to the spelling and saying, “It’s this one!” This is /s/. The process is now repeated for the second sound /a/ and then for the third /t/.

When the word is built and we have the spellings s a t, sitting on the three lines. The teacher now asks the class to say the sounds and read the word. Every child says, /s/ /a/ /t/, ‘sat’. The teacher then asks several children she knows will have success in saying the sounds and reading the word. As they do this, the teacher is gesturing to each spelling. Having seen the process modelled a number of times, the teacher can ask a child for whom this is new learning to repeat the sounds and read the word. Repetition is essential to get the knowledge being taught into long-term memory and to taking those first steps towards automaticity.

Every day, the teacher should choose four or five children to repeat this highly interactive process by saying the sounds and reading the word. In this way, the teacher makes sure that every child is able to do what is being asked and also that every child gets the kind of rehearsal, practice and repetition they need for learning to become permanent.

After the word has been read, the teacher removes the squares and asks the children to tell her the sounds in ‘sat’. As they tell her, she writes them, thus providing a model of how the letters/spellings are formed. Then, to check that the class got what they were asked for (The word ‘sat’) the children say the sounds and read the word, the teacher gesturing to each spelling as they do. When the sounds /s/ /a/ and /t/ are said precisely and as a class, the word ‘sat’ can be clearly heard, thus confirming that the children got what they wanted.

Finally, with the word still on the whiteboard, the teacher asks the children to draw three lines on their board and show her their boards. Next comes the writing. The children now write the word by saying each sound as they form it on the line provided. After they’ve finished writing, everyone puts their finger under the first line and, in unison, the class says the sounds and reads the word. Naturally, there will be children who will need help in forming letters but, at this point, as long as the spelling looks something like it should, it can be accepted. Thus, a letter < t > may look like a cross but, for now, it can pass. Work on letter formation should be done at another time.

Can you expect this process to go smoothly from the start? The short answer to this is no! It will take some children time to grasp the format of the ‘game’ (because that’s what it is) and some will take longer than others. Teachers need to remind themselves just how much effortful practice goes into learning a new activity from scratch. In laboratory activities involving unfamiliar materials, even adult participants evidence surprisingly poor performance.

So, just to summarise how carefully we’ve been to follow the kind of advice supported by cognitive scientists, such as John Sweller et al, what we’ve done is:

- introduce only three items for children to learn, thus reducing cognitive load

- begin to give practice in the procedural learning skills of segmenting and blending, skills the children will need all their reading lives

- begin to build a schema for sounds and spellings

- keep down the amount of teacher talk to a minimum and made sure that the language used is accurate

- introduce a simple lesson template which will serve to introduce new elements of learning: < m >, < i >, etc, etc.

- challenge the children to combine their auditory, visual and oral skills in a way that offers success very quickly.

Photo by nicollazzi xiong from Pexels